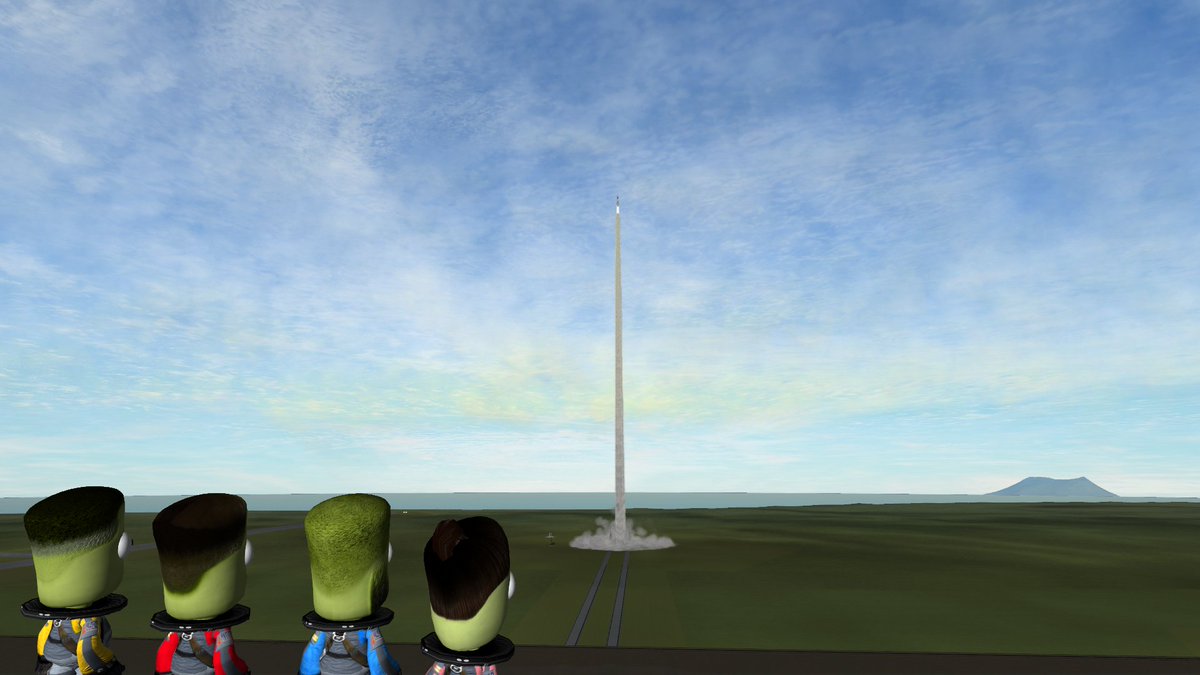

Hello everyone, Drew Kerman here, Operations Director for the KSA. I’d like to take some time to explain why despite the fact that we’ve been going to space now for over three months we haven’t taken any photos from above the atmosphere and won’t be doing so for another few months at least. Although it’s true space photos would not be a huge science return and mainly be of benefit only to our PR department (do we have a PR department? I should know that) that’s not the reason. Simple fact is that our current fleet of sub-orbital rockets, the Progeny family, are not a good platform for taking photos for numerous reasons.

Hello everyone, Drew Kerman here, Operations Director for the KSA. I’d like to take some time to explain why despite the fact that we’ve been going to space now for over three months we haven’t taken any photos from above the atmosphere and won’t be doing so for another few months at least. Although it’s true space photos would not be a huge science return and mainly be of benefit only to our PR department (do we have a PR department? I should know that) that’s not the reason. Simple fact is that our current fleet of sub-orbital rockets, the Progeny family, are not a good platform for taking photos for numerous reasons.

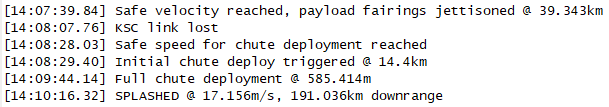

The main reason is that because they are unguided ballistic rockets in order to help maintain stability during powered ascent their fins are slightly angled to spin the rocket up. This is a very easy way to keep a rocket flying straight and stable but because we are using the fins to induce spin rather than, say, small external thrusters, the spin rate increases throughout the entire flight while the rocket is under thrust. By the time the third stage has expended its fuel the rocket is generally spinning at a rate of ~150RPM or nearly three times per second. To get an idea of what that would look like, here is a video taken during a Progeny Mk2.1 launch where the payload was only spinning at roughly 120RPM. Any photos taken at such speeds would be extremely motion-blurred, especially given the longer exposures we would want for photos from space.

A solution to this problem comes from a technique known as a yo-yo despin, which you can see an example of in this video simulation. Progenitor engineers have already modeled a similar setup and determined it’s possible to get this to work for the Progeny rocket by removing the batteries on the upper payload truss to install two winch units that would deploy the counter-weights once the payload is in space, slowing down the spin rate so that a single camera mounted on the lower truss (the other payload position would be a battery) could get shots of various views as the rocket rotated more slowly. However to deploy the counter-weights means detaching the upper payload fairings, and that could bring about a new set of problems.

We keep the payload fairings attached for several reasons: they protect the internal parts during re-entry, allow for a more aerodynamic return from space and remain airtight to help the rocket float after splashdown. Removing the upper fairings (camera would peer through a window in the lower fairings) would allow re-entry heat to enter underneath the packed parachute, possibly melting it unless we reinforced the underside. Turbulence caused by the open top half of the payload bay could possibly cause the rocket to tumble on re-entry. If splashdown occurs faster than normal for any reason, the empty fuel tanks are designed to crumple and take the impact to protect the payload but that will reduce their ability to help the payload float and lack of an airtight payload bay would further reduce the chance of the payload remaining on the surface for recovery.

Knowing we may not recover the payload, we could have the camera transmit its data back to KSC, but this would drain the electrical supply pretty quickly even with low-res black & white images, moreso since the rocket will be flying with one less battery than normal. Unfortunately the potential loss of the payload far outweighs the potential gains, especially considering the payload contains all the reusable parts of the rocket (parachute, payload trusses and probe core).

Even placing a streamlined camera outside on the third stage pointing downwards is not something engineers want to attempt, due to the fact that in all recent flights the third stage has never failed to pickup some precession in its roll, wobbling around its prograde vector. Anything on the outside that could further increase this effect is not something the team wants to consider. They are however open to the idea of a camera on the second stage booster, which with the Block I and Block II may be able to travel higher than a KerBalloon, which has returned our highest photos above Kerbin so far from 24.9km.

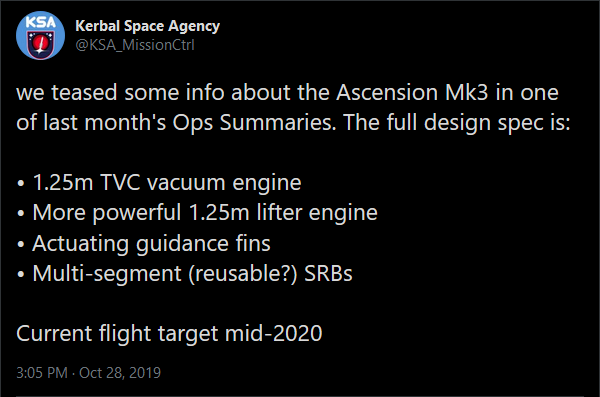

Ultimately I’m afraid those waiting for cool space photos will have to continue to wait until early to mid next year when our orbital program starts to take flight, as that rocket will be steerable both during ascent and in space to allow us to grab some really cool shots. Sorry we can’t make it happen sooner, but at least now you know it’s not for lack of trying!